Fausto Novelozo, chief of the Taw’buid tribe, exhales from his worn clay pipe. The sweet scent of wild tobacco envelopes the hut. “It was sickness that drove us down from the mountains. Measles we got from Tagalog visitors. Half our village of 200 died. The survivors moved here to be closer to civilization. Now we constantly need medicine.”

We’re in Tamisan Dos, one of two newly-established villages flanking a road which leads to the Iglit-Baco Natural Park in Occidental Mindoro. In their tongue, Taw’buid means ‘people from above’ because they historically inhabited the island’s mountainous interior. Fausto’s people are highlanders no more.

Before we push deeper into the park, we leave the old chief some provisions – coffee, sugar, salt and a small bag of medicine.

The Danger Of Disease

When imagining threats to biodiversity, wildfires, logging, poaching and other visual activities are top-of-mind. But sometimes, the smallest beings do the most damage.

Disease is a major killer of isolated tribes. In July of 1837, an American steamboat called the Saint Peter infected the Mandan, a North American tribe of about 2000, with smallpox. Three months later, only 23 were left alive.

“Isolated communities are especially vulnerable to diseases from the outside world because immune responses have yet to be developed,” says medical anthropologist Dr. Gideon Lasco. “Limited access to health care and fear of hospitals also keeps them from seeking treatment.”

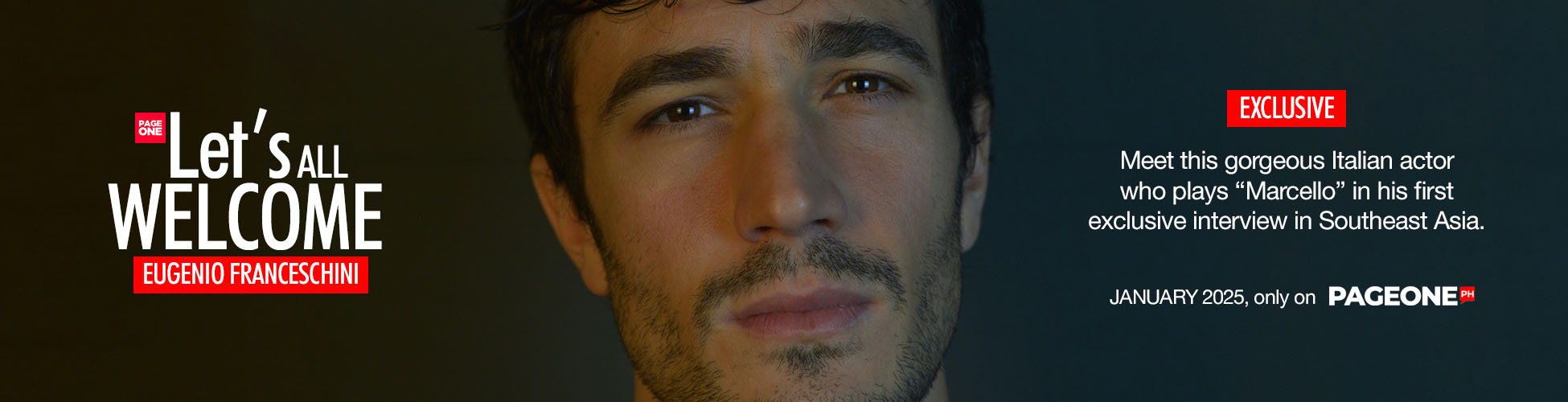

The Taw’buid are just one of many groups that the Tamaraw Conservation Programme (TCP) works with in their 40-year old bid to save the tamaraw (Bubalus mindorensis), a well-known but critically-endangered buffalo found only in the Philippines. Like native tribes, the tamaraw is highly-vulnerable to disease.

Decimated By Rinderpest

Once, tamaraw grazed by the thousands. An estimated 10,000 inhabited Mindoro at the turn of the century.

As now, Mindoro then had prime-pastureland – so good that ranchers imported thousands of cattle to the island. As grazing competition for the lowlands increased, ranchers started herding their cattle up mountains – the same ones occupied by tamaraw.

In the 1930s, an outbreak of rinderpest took place. A deadly virus which kills 90% of what it infects, rinderpest laid waste not just to the population of farmed cattle, but wild tamaraw as well.

By 1969, numbers were estimated to have dropped under 100, prompting the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to declare the species as critically endangered – just one step above extinction.

Decades of conservation led by the TCP, Biodiversity Management Bureau, Mounts Iglit-Baco Natural Park (MIBNP) and a host of allies including the Biodiversity Finance Initiative (BIOFIN) of the United Nations Development Programme and Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Mindoro Biodiversity Conservation Foundation Incorporated, D’Aboville Foundation, Global Wildlife Conservation, World Wide Fund for Nature, Far Eastern University and Eco Explorations, have helped tamaraw numbers recover to around 600, confined to four isolated areas in Mindoro. All are vulnerable to disease.

“Bovine tuberculosis, hemosep and anthrax can enter Mindoro if we’re not careful,” explains Dr. Mikko Angelo Reyes, a Mindoro-based veterinarian. “The key is biosecurity, the prevention of disease through quarantine, inoculation and immunization. We should ensure that at the very least, animals entering the island are checked for sickness. We should also establish and respect buffer zones around protected areas, which are often rung by farms and livestock.”

The Mounts Iglit-Baco Natural Park (MIBNP), a former game refuge turned into a protected area, spans 106,655 hectares. It is home to the Philippine brown deer (Rusa marianna), Oliver’s warty pig (Sus oliveri) plus many other rare and endangered species. It also hosts 480 of the world’s 600 remaining tamaraw.

It is also currently surrounded by 3000 cattle belonging to 30 ranchers.

Rangers Need Help

Together, TCP and MIBNP rangers work to ward off invading cattle or heavily-armed poachers. They constantly dismantle spring-loaded balatik and deadly silo snare traps while discouraging the park’s indigenous Taw’buid and Buhid tribesfolk from engaging in slash-and-burn farming.

“It’s no easy task since the tribes must feed their growing families,” says TCP head Neil Anthony Del Mundo. “As their numbers swell, so do their requirements for space and food, which is why they’re setting-up more traps, even inside core zones. This is a challenge faced by all protected areas inhabited by people.”

The life of a tamaraw ranger is fraught with difficulty – the risk is high, the pay low.

TCP was created to bolster tamaraw conservation efforts in 1979 through Executive Order 544. However, it was set-up as a special project instead of an office, so only its head is a regular employee with benefits.

In 2018, TCP was allotted PHP4.2M for operations. This 2019, the budget was slashed to PHP3.3M, 75% of which goes to personnel salaries, leaving little for operational and field expenses.

Despite the fact that most rangers have put in an average of 10 years’ service and stay in the field a month at a time, none of them get benefits despite years of dangerous fieldwork.

“TCP must be institutionalized as an office to secure better pay, permanent tenure and government benefits for its hardworking rangers.

Our tamaraw rangers go out against hunters armed with military-grade rifles. Communist rebels pass through the same places they patrol.

Poisonous snakes, charging tamaraw, animal traps, dangerously-swollen rivers … every time our boys go out on patrol, one foot’s already in the grave,” adds June Pineda, former TCP head and now a Community Environment and Natural Resources Officer (CENRO) based in Mindoro.

To gather much-needed resources for TCP and various protected areas nationwide, BIOFIN is helping raise funds via bank account donations to Metrobank account number 750-001-5620.

“A little help goes a long way. We ask fellow Pinoys to donate just a bit to save the tamaraw and the rangers keeping them alive and kicking,” says BIOFIN Philippines project manager Anabelle Plantilla. “Through their efforts and sacrifice, they have managed to grow tamaraw numbers from 100 to about 600.”

Since its inception in 2012, BIOFIN has worked with both the public and private sectors to enhance protection for the country’s biodiversity hotspots by helping secure funds to implement sound biodiversity programs.

The Iglit-Baco Natural Park exists in a fragile balance. To keep its people, animals and ecosystems healthy, we all need to pitch in. Donate via the details below.

Metrobank Account Name: Mindoro Biodiversity Conservation Foundation Incorporated.

Current Account Number: 750-001-5620.